The Southern California coastline is in crisis.

It is predicted that up to 67% of beaches may disappear by 2100 and increased flooding is likely to occur due to extreme erosion, sea level rise and expanding urban areas.

Due to a long history of pollution and urbanization, wetlands and estuarine ecosystems that once protected the coastline from these threats are rapidly disappearing and degrading.

Traditional efforts to protect our coastline use concrete structures, but these efforts may harm local ecosystems. Living shorelines are a creative alternative approach that promotes the restoration of naturally occurring species. Upper Newport Bay (UNB) is one of the first locations in Southern California to construct a living shoreline and is restoring native eelgrass and the severely threatened Olympia oysters.

Oysters are an ideal organism to construct living shorelines because of their ability to build large beds with layers of shells and the ability to filter water.

Growing native Olympia oysters.

The structure of the beds prevents erosion, stabilizes shorelines and provides a new habitat. Meanwhile, the individual oysters filter feed which improves water quality.

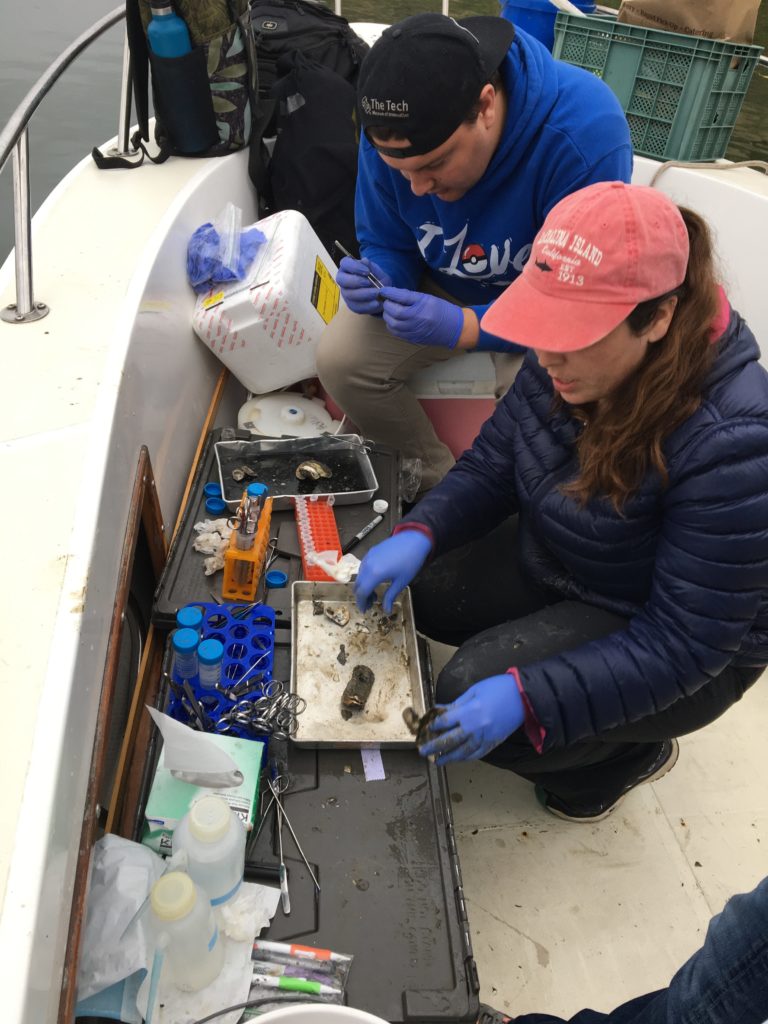

In collaboration with the OC Coastkeeper, California State University, Long Beach and California State University, Fullerton are researching which stresses may be present in restored oysters. Olympia oysters were collected in early March from each bed at each of the four living shorelines restoration sites in Upper Newport Bay.

Gill tissue was dissected from the collected oysters to analyze cellular signals and the remaining tissue was used to measure pollutants. This analysis will show if oysters from beds paired with eelgrass restoration contain a greater concentration of pollutants than oyster beds without adjacent eelgrass.

Amanda Russell and Ethan Eisenhart dissect recently collected oysters to collect tissue samples for analysis on the OC Coastkeeper boat.

Eelgrass can increase sediment accumulation, which prevents erosion but also traps pollutants. It’s possible that the presence of eelgrass may lead to an increase in localized pollutant concentrations along with this additional sediment.

By comparing the results of these tests, this study can help us begin to understand how oyster health is affected by the living shorelines plot designs, and if pollutants play an important role. Through this research, we may find new insight into how to improve the efficiency of restoration design and living shorelines as well as pollutant dynamics in California.

Check back for more updates, and to see what this team can discover!

About the Author:

Amanda Russell is a current master’s student in the Holland Toxicology Lab at California State University, Long Beach, California.

She is passionate about everything oyster, and is studying how their health is affected by changes in their environment. Amanda is excited to engage community members with conservation and inspire others to discover the ecosystems and wildlife in their backyard. For more information, contact Amanda at amanda.russell@student.csulb.edu and visit holland-toxlab.com.

Amanda Russell holds an oyster on the OC Coastkeeper boat.